IR Part 2: Operationalization of Interplanetary Relations

Refining the Research Approach - Empirical Coherence, Theoretical Implications and Practical Purposes

*This is part two of the broader, bi-weekly appearing International Relations examination of the Star Wars universe. Part one can be found here.

If we are to conduct serious research in a completely fictional universe, some issues and valid concerns must be acknowledged. First of all, those who reason against the probability of a human, galactic government ignore the significance of preceding changes to world - and solar system – politics. The state for instance, is no longer the only political force to be reckoned with: private companies are at the forefront of exploring space as much as international regimes like the ISS or UNOOSA – the space agency of the United Nations. If political science seeks to provide valuable insights to how decision-makers should proceed in this changing environment, its theories must adapt and improve too.

Why then must we involve all sides of the force known as international relations theory, not just the dogmatic approaches of some? The lack of a single, central paradigm hints at the underperformance of our theories to fully predict modern international politics yet. Nonetheless, they provide us with the working bases on which any subsequent coherent scientific inquiry currently builds. Expanding the ecosystem of political interactions to a whole galaxy then certainly presents an exogenous shock to these paradigmatic assumptions, and challenges these models to adapt to entirely new circumstances. We may thereby discover current theoretical impasses more easily, by stripping away the disguises of stock-standard historical evidence.

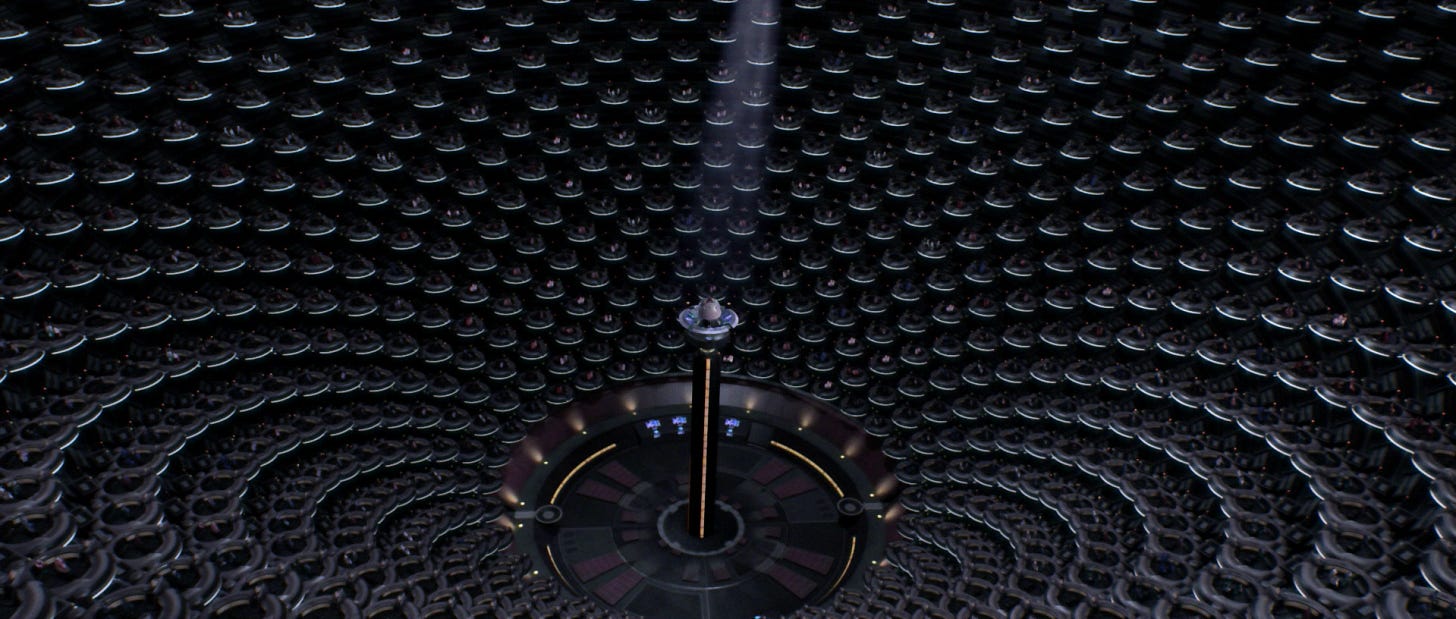

Star Wars provides us with such an environment systematically different from our earthly conditions. Science fiction as a whole generally takes existent challenges, ideas or technological capabilities, end extorts them to an extreme degree. In this particular case we encounter unprecedented political entities, including planetary authorities, but also galactic organisations with a considerable amount of power; the Palpatine’s galactic empire in particular must be mentioned here. This poses fascinating challenges to our conventional depiction of the international system as anarchical, states as primary sovereign actors, or what constitutes a topic of interest for the academic discipline. Subsequently, it is a sufficient stress-test to our theories’ explanatory leverage.

To highlight just some of the more relevant questions for IR here:

Is the Star Wars universe characterized by the absence of a central, powerful and controlling entity like our international system, hierarchies based on repression and violence, or an entirely different conceptualisation?

Are the Republic, the Hutt-Space or Imperial Empire better understood as equivalent to our modern nation-state, or rather as a more developed international organisation akin to the United Nations? How important are these classifications to the operation of our conventional theories?

What constitutes a regular theme in interplanetary relations? Can we, for example, incorporate concerns about intelligent droids or clones and non-humans as a subsection to human rights or do we require new categories?1

Do intergalactic individuals behave according to a logic of consequences or appropriateness, and how does the force fit into such frameworks?

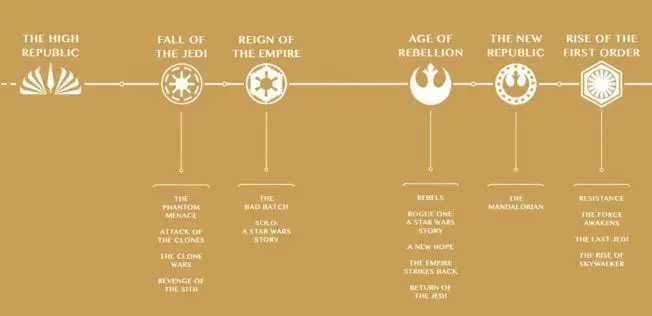

Disney and the Canon-Problem

However, a second issue consequently concerns the correctness of our datasets and empirical evidence. Star Wars suffers from a schism between mythical accounts and the official narratives postulated by Disney. This conflicted canon is a significant obstacle to coherent definitions and interpretations of galactic developments. I choose to disregard this division to the extent that both timelines can be examined separately from one another. Legends, originally, were designed to be canonical and consequently did not fundamentally alter the dynamics of the movie-universe. The increasing formal acknowledgement of former Legends-material in official Disney-history, including individuals like Thrawn and political regimes like the New Republic, further serves as a testament to Legends’ value as source material.

Critics may argue that this operationalization allows for substantial variations of how natural process are conceptualized respectively. Among recent developments for example, has been the alteration to lightspeed travel, for ships to be able to affect others in and outside the hyperspace in The Last Jedi. However, even George Lucas’ original historical accounts entailed minor contradictions, including whether the force was an energy field or rather result of biological activities of midichlorians. I argue that these minor conflicts merely mirror our disagreements and gaps within academic advances on earth’s natural laws and are therefore of equal importance to the development of a model of political interactions.

Of course, progress in the understanding of the surrounding ecosystem and its natural mechanism cannot be totally disregarded. Military tactics must adapt to according changes in the conduct of warfare, economics to implications for supply chains, or biologists one day may convert non-force-wielders on a galactic scale, with serious consequences to the whole galaxy. No doubt, these issues must be and are discussed separately, but they are not of primary importance to the examination of the interplanetary political system as a whole.

For instance, force-users like Jedi and Sith remain significant non-governmental organisations interacting with planetary or galactic authorities. International relations theory then focuses less on how they acquired their native power capabilities, but rather how and why they use them. Discussions about whether or not “[t]hat’s not how the force works!” are as important to IR theory, as the technological operation of an ICBM is. Instead, IR theory would seek to explain why Jedi or Sith use their power to combat each other, instead of signing peace treaties and regulating the recruitment of new apprentices or force-drain processes under the auspices of a neutral senate committee.

Furthermore, some would criticize that the diverging chronologies between non- and canon-material presents a case of compromised evidence. However, in both cases empirical evidence is complete within its respective sphere and testing theories against a specific example provides us with a set of variables to be examined. Evidence for a transition of the rebellion into a functioning New Republic can be taken into account just as much as material concerning the creation process behind the Resistance. Consequently, the interpretative disagreement is irrelevant, as long as the narratives’ borders are acknowledged and respected. The subsequent multiverse can therefore be navigated experimentally, meaning outcomes result out of fixed historical socioeconomic conditions just like on earth.

The following pieces in this series will consequently continue exploring how international relations theory can explain the developments in a galaxy far, far away. We have shown that Star Wars is an ideal starting point to further develop our theories beyond earth. We can dismiss discussions of inexplicable natural laws and canonical correctness as obstructive to their application. Be it the nature of the force or the diverging pathways taken by the New Republic for example, galactic orders must still consider how to respond to Sith-spawned threats of a galaxy in darkness.

How supportive are IR theories as guidelines in crafting an effective policy response? How should such an interplanetary security policy ultimately be designed?

The issue of droids fighting for their rights was actually rather frequent. Rebellions were launched not only on Kessel, as depicted in Solo, but also on several other occassions, most notably during the droid revolution.